Let me get this out of the way: I’m going to maintain a semi-regular Substack. If it’s anything like my children and my plants, I’ll keep it alive, though it probably won’t get the attention it deserves.

With that, a few words on Rickey Henderson, who passed away over the weekend.

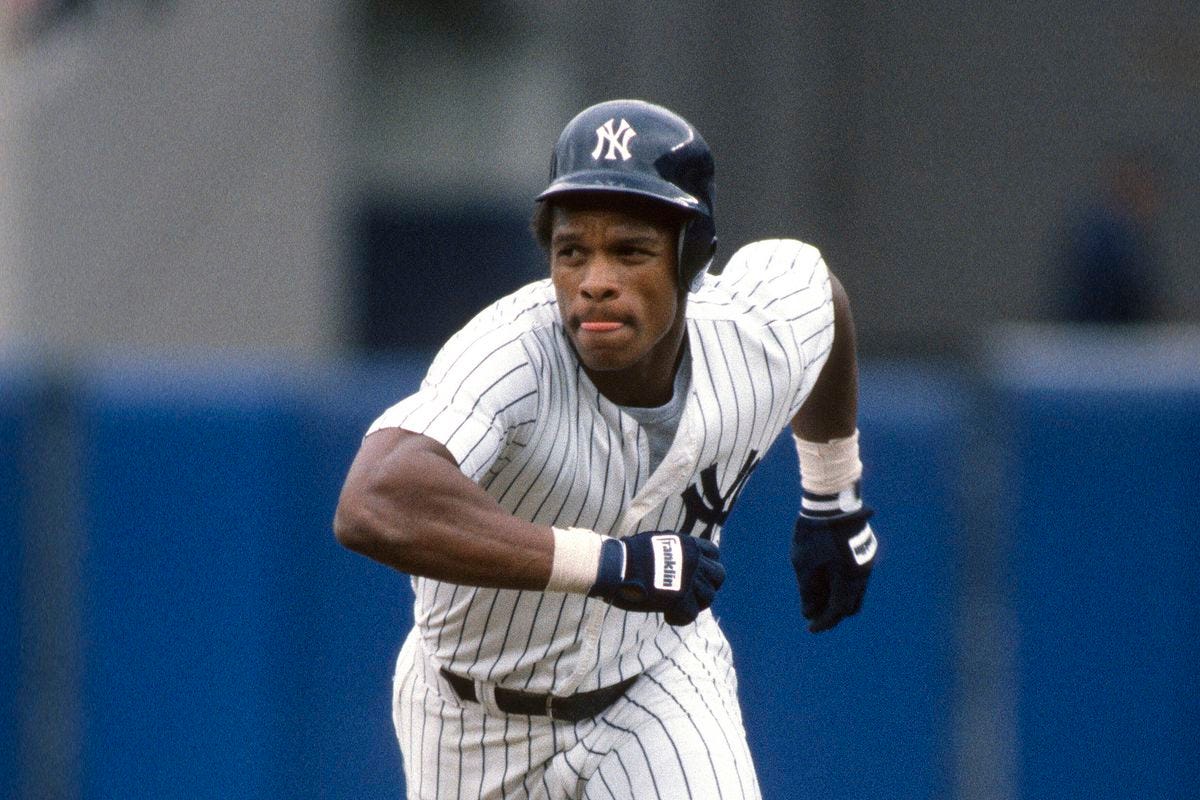

Rickey famously played for 25 seasons and nearly as many teams. To the extent such longevity makes any sort of sense, it did for him, considering his body always looked like a compact, coiled muscle, ready to explode at a given moment. He was called the Man of Steal for all the stolen bases, but the secondary allusion to Superman’s physique made for an apt comparison.

Henderson is most generally associated with his hometown Oakland Athletics, the team for whom he played his first six seasons, including the 1982 campaign in which he stole an insane 130 bases. He would later play three more stints with the A’s. As much as any athlete other than perhaps Marshawn Lynch, his identity is tied to Oakland, that weird and proud and grimy city that exists in the shadow of its more beautiful and accomplished sister across the Bay.

I got to know Rickey as a Yankee, however. Coming of age as a baseball fan in New Jersey in the mid- to late-1980s, I bore firsthand witness to one of the rare periods during which the Yankees and Mets were both competitive at the same time. The story goes that the Mets were a juggernaut, while the Yankees were a perennial contender that couldn’t get over the hump, though this is a bit too tidy of a summary. Because they won a very memorable World Series, people forget that the Mets were often an underachieving mess from 1987-90. And because this was the Steinbrenner-On-Bath-Salts Era of firing managers and hiring private detectives to torture Dave Winfield, people forget that the Yankees were consistently a very strong team in a very tough A.L. East.

In any event, the Yankees and Mets of the mid-to-late ‘80s were concurrently good teams, which is a bit of an anomaly as far as those two outfits go. And it made for an exciting time and place to be introduced to professional baseball.

I was a Mets fan. It was easier. They won more, their players were in more commercials, and their uniforms appeared to have been designed by a grade schooler.

My father was a Yankees fan. He adored Don Mattingly, just as he’d adored Thurman Munson and Mickey Mantle before. Consistent, no-frills excellence.

Rickey Henderson was the Yankee that even the Mets fans loved. There are plenty of reasons for that, and many of them can be explained by Henderson’s gaudy stats and the kooky stories you’ve been reminded of over the past few days—John Olerud’s helmet and the framed paycheck and the John 3:16 thing. It’s all legit, or at least it should be.

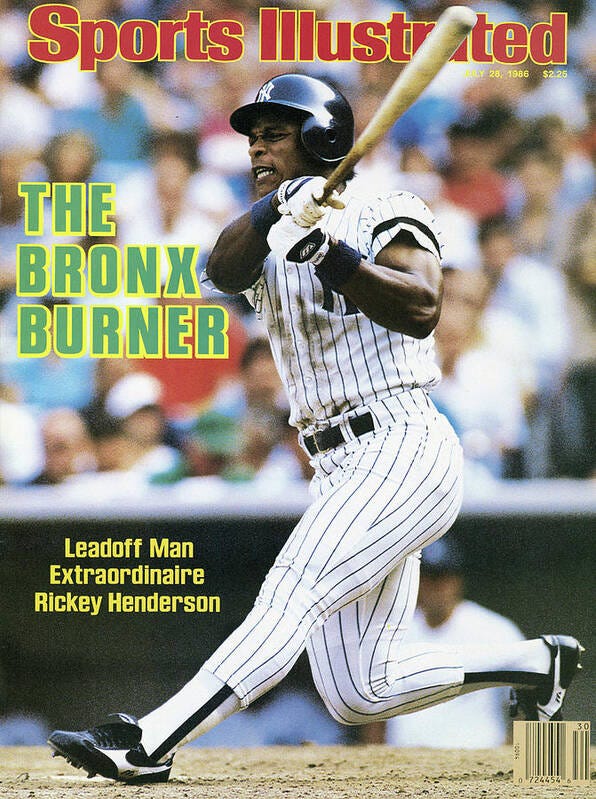

But putting aside the numbers and the stories, my love of Rickey was based on something much simpler and more intrinsic: He was the coolest looking cat on the field. It’s too simple to say that MTV and Nike were redefining what it meant to star, and that style was suddenly becoming just as important as substance. Style has always mattered. Well before Rickey’s time, Willie Mays and Joe DiMaggio certainly had enough of it to match their abilities, and each was celebrated accordingly. But in that time after Reggie Jackson and before Ken Griffey Jr., it was Rickey, more than anyone else, who was baseball’s most perfect combination of style and substance. He played with the brightest flash. And more than that, he played historically well with that flash.

There are all the stolen bases. There are all the leadoff home runs (and all the sloooooow trots around the bases). There are all the routine leftfield catches snatched out of the sky with a snap, a move that undoubtedly broke more than a couple noses of kids trying to emulate Rickey’s swag. It made for a fun package.

This video, complete with a puzzling and awesome Boney M. accompaniment, does as good a job as any I’ve seen of conveying Rickey’s whole thing:

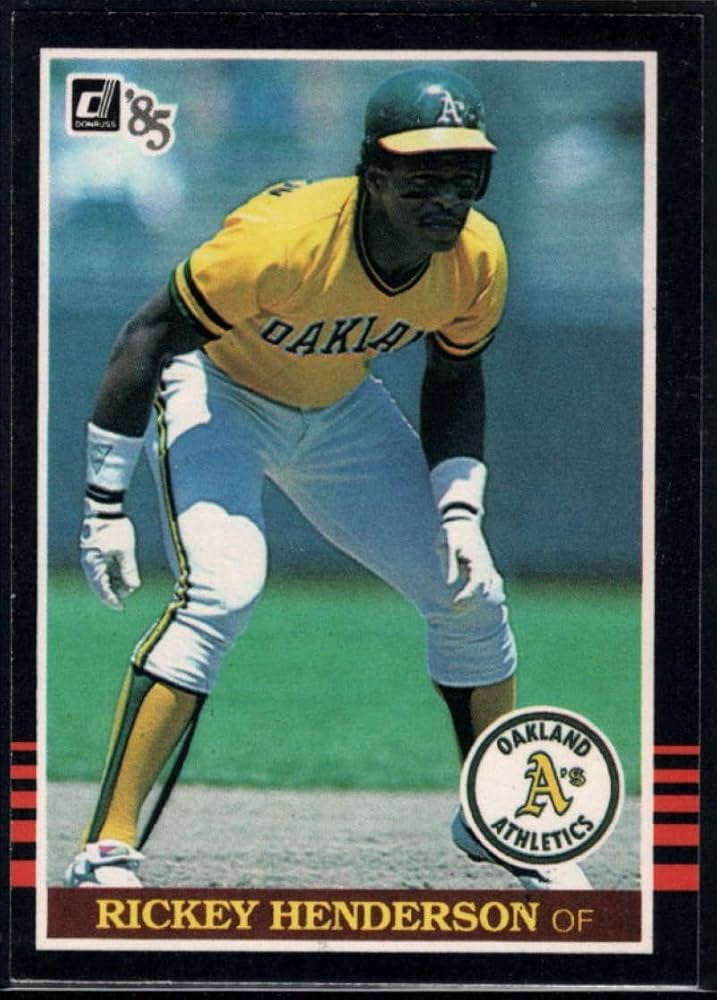

Rickey’s baseball cards are testament to that style, too.

This was paradoxically the apex of baseball card collecting and the heyday of boring looking baseball cards. Throughout the ‘80s, Topps would take a few hundred headshots during spring training and barf out some of the most insipid looking cards you could imagine. Fleer was even worse, and Donruss generally wasn’t much better. It wasn’t until the tail end of the decade that Upper Deck and Score crashed the scene and decided that action shots were actually a pretty fun idea.

Yet even card photographers of that time realized that you couldn’t take a picture of Rickey that didn’t at least convey some feeling of energy, some premise of anticipation. Even when standing still, it always felt like something was about to happen.

Also important was that this was still the period of gorgeously colorful jerseys. Having the most electric player’s cards shining in neon yellow and green—colors that actually feel electric—certainly didn’t hurt his aesthetic appeal.

At the risk of sounding like a bitter old man (kinda guilty!), my childhood also happened to be the last great time to fall in love with baseball. As things currently stand, Major League Baseball is awful. Baseball as a sport isn’t awful, but the product known as professional baseball that we are forced to consume most certainly is. I’m not even sure that’s debatable. Every article about baseball basically amounts to “why don’t people like baseball anymore?” Every metric that I ever come across concerning the game’s health, whether measured in viewership or participation, indicates that the sport is losing ground, and dramatically. I can’t name you the last five World Series champions, and I’m the type of person who should be able to readily name you the last five World Series champions.

You can blame that on all the obvious things wrong with the game itself—the boring pace of play; the pitch counts; the three-true-outcomes approach to hitting; the lame-o Moneyball strategizing. Or you can blame it on the softer stuff—the way that steroids bastardized the history of a sport that lent itself to history nerds (ahem) more than any other; the way that modern ballparks now make you feel like watching the game is a secondary concern; the way that that players no longer feel particularly relatable, whether because of the crazy money or the language barriers or the free agency. It’s hard to pinpoint exactly when it happened, but like how Hemingway described going broke, it happened gradually, then suddenly. And what’s left is an inferior product to what I and so many others fell in love with.

But in the ancient world, in that hazy land of complete games and triples and Astroturf and everyone wearing powder blue jerseys, in that time before Jordan and the NBA put a stake through MLB’s heart and before the NFL’s dominance was a foregone conclusion, in baseball’s last great time to be a star, Rickey shone brightest.

And it’s in that world where he’ll forever exist, taking an obscene lead off second, his green Mizuno batting gloves visible from space, knowing just as well what the pitcher and catcher and everyone else in the entire stadium knows—that he’s about to steal second and that no one is going to stop him. And he’s probably going to take third after that. He will forever be anticipation and action and force.